- Home

- Jean Guerrero

Crux Page 15

Crux Read online

Page 15

* * *

•

In eighth grade, when Matt and I were comparing report cards, he said: Remember when you had your hair short in sixth grade? It looked nice. You should cut it again.

I begged my mother, for perhaps the hundredth time, to let me cut my hair. My friend Elizabeth was no longer around to make me feel good about it. Her parents had sent her to an all-girls boarding school on the other side of the country. Give me one good reason and I swear I’ll never ask you again, I implored.

Because I like it, my mother said.

Oh, that’s a great reason. Because you like it, I have to be miserable.

She was in the kitchen preparing a salad with Abuela Coco. My intemperate tone provoked my grandmother. She lunged at me with the knife she was using to chop lettuce. Irrespetuosa! Abuela Coco hissed.

I retreated from the knife. Oh my god, you’re insane!

My mother wiped her hands on a kitchen rag, rolling her eyes. No, Jean, you are, she said. If you want to cut your hair, go live with your father. While you’re under my roof, you have to follow my rules.

I felt a wave of anger surging from the floor through my head. I screeched: Bitches! Abuelo Coco stood from his wheelchair, stumbled toward me, and slapped me on the mouth. I was shocked into silence. His slap was soft, almost a tap, but the unexpected nature of the action, the effort it took, sent a clear message: I was a bad, worthless girl…in spite of all my studying. Tienes que respetar a tu madre, he said in his deep voice, his eyes crinkled and watery, containing in them all the pain in the world. I burst into tears. If sanity was the Cocos, I decided, then sanity made no sense. For the first time I could remember, I felt allied with my father.

* * *

•

I have found one of the crossroads: it is here that Papi’s absence reached maturation in me, and began to bear fruit in my body. How common is this crop. Eighty percent of single-parent homes are empty of the father. The disadvantage for the son is obvious: he lacks a role model. For the daughter, the damage is harder to define. It is refractory: The daughter sees her single mother slaving away, weighed down by love and duties. She is the girl’s model, her future: toiling and tired and trapped. The absent father’s magnetism lies, in part, in the contrast he represents. He is not tied down by anything. He has a freedom and a power she covets. Slowly the girl becomes aware of the borders of her female body. She begins to erase them. She conjures the absent father in herself.

* * *

•

My mother learned she had once more failed to pass her internal-medicine board certification exam, despite our prayers. I realized the God of Catholicism was a fiction—like the Animorphs and like the Confessors in The Sword of Truth. I had no need to fear the wrath of Lucifer. I informed my mother I was a Wiccan. When she protested, I argued it was my constitutional right to practice the religion of my choosing. I needed to arm myself against the Cocos. I opened my jewelry box and retrieved my old Animorphs necklace, a silver square pendant with an emblazoned A. Using water and candles, I repeated the following spell thrice: I cast a spell upon this item thrice, to protect me through my daily life. Earth, wind, fire and sea—as I say so mote it be.

I slipped it over my head. Immediately, I felt the buoyancy of a protective orb. I curled up with my latest Sword of Truth book and materialized inside the Midlands, where the Seeker of Truth was hacking away at cackling evil creatures. Abuela Coco’s screeching brought me back to the suburbs. Ya está la comida! I touched my necklace with a smile, knowing I was safe. But as I walked downstairs, I tripped. Pain shot up my knees and elbows as I crashed against the marble floor. Purple bruises bloomed like monstrous roses on my joints. I had never fallen down the stairs before. It was a curse from the spirits, a warning: the supernatural was not my realm. I took off my necklace and wept. Not even witchcraft could save me.

* * *

•

Papi invited Michelle and me on an excursion to Tijuana. We were sure Abuela Carolina had talked him into it. Every time we visited him, he greeted us with vexation—if at all. We ate lunch at a seaside Mexican restaurant filled with free-flying birds in nervous silence. On the beach, a man with a sombrero held a group of skinny horses. Our father asked, in an unexpectedly chipper voice: Do you girls want to go horseback riding? I had wanted to ride horses since I was a little girl, a symptom of my fairy-tale diet. We climbed onto three horses. Michelle was scared, so the caballero assigned her his most tranquil steed. A group of drunken teenage tourists scrambled onto the remaining horses. We followed the caballero along the shore. Suddenly, my father broke his horse into a gallop with a holler that sounded like Hya! As if afraid of being left behind, all of the horses bolted after his, except my sister’s, which dragged its feet. I lost my stirrups. People screamed. An intoxicated tourist toppled off his mount. At first, I was terrified. I bounced violently in the saddle. But as my horse’s stride lengthened, it became loping and smooth. I understood, suddenly, that all I had to do not to fall was not be afraid—I had to move with the horse rather than against it; I had to incorporate its power into my body. The wind lashed my face with particles of the sea as I pursued my father. My horse’s hooves splashed in the waves. I felt like the young warrior, Atreyu, galloping through Fantasia in The Neverending Story. We were racing through the Swamp of Sadness, too buoyed by adrenaline to sink. Papi pulled on his horse’s reins and spun it around. He saw me coming. As my horse slowed bumpily, I thought, with horror, that I was going to fall right in front of my father. I moved as best as I could with the horse as it halted. I stayed in the saddle. Papi said: You’re a natural.

* * *

•

A few days later, I awoke in the middle of the night. My bed was shaking. I was unsure if it was an earthquake or demons. In my journal, I described it this way: I was really scared and then I like, FELT, not heard, but FELT this voice that wasn’t really a voice saying but not really saying…“It will pass” in a reassuring way. I felt a wave of calm and fell back to sleep. In the morning, I walked downstairs. Abuelo Coco was watching the television from his wheelchair. I saw a plane flying into the World Trade Center in New York City. It was September 11, 2001. The apocalypse had come. Real-world villains weren’t Yeerks or black-magic wizards. They were terrorists.

* * *

•

At night, Abuela Coco snuck out of her room into the backyard and tapped on the sliding-glass door of the living room to scare me and my sister while we watched television. It was pitch-black outside, so we couldn’t see her out there. We scampered out of the room, limbs everywhere, bloodcurdling screams. The tapping started happening regularly. We told our mother about our psychopath stalker, but she just rolled her eyes. She said we were imagining things, we were “being Schizophrenics,” like our father.

* * *

•

On September 20, I was in bed reading The Sword of Truth, envisioning myself as the Confessor galloping bareback into war. My mother threw open my door. Her lips were taut and pale; her eyes seemed too wide for their sockets. It was a new expression that was becoming familiar to me, but it made her unrecognizable as the soft, sweet mother of Paradise Hills. She sniffed. You’ve been smoking in here, haven’t you? I gawked. She might as well have accused me of orchestrating the 9/11 attacks. Mom, can’t you see I’m reading? She shook her head. She said, with disgust: It’s the marijuana, isn’t it! She stared right through me. Look at this mess. You can’t even clean your own room. You need to see a psychiatrist. You’re Schizophrenic, just like your father.

* * *

•

A few years later, in high school, I wrote a paper on self-fulfilling prophecies. One of the founders of sociology, Robert K. Merton, coined the term. A photograph shows a white-haired man with a friendly face and prominent forehead. In his 1948 article “The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy,” he boils it down to this: “The self-fulfilling prophecy is, in the

beginning, a false definition of the situation evoking a new behavior which makes the originally false conception come true. The specious validity of the self-fulfilling prophecy perpetuates a reign of error. For the prophet will cite the actual course of events as proof that he was right from the very beginning.”

How strange and sinister, the power of fear—the way it’s rooted in love.

SELF-FULFILLING PROPHECY

Mommy was turning into Mom. She was harder than her previous incarnations. She had taken off my father’s engagement ring a decade ago, but her fingers were covered in metal: her Service Corps ring, medical school ring, university ring, high school ring. I no longer craved her touch. I felt displaced by her body. When she looked at me, her eyes demanded so much that they seemed to vacuum up my strength. I could feel her in my breath, in my sweat. Her anxiety was in my chest, her disappointment in my teeth. We knew each other’s phases and imperfections as if from the inside. My father, in contrast, was a mystery. A question mark. I pondered Papi like the riddles in The Sword of Truth. I was eager to unravel him. I thought of him as enlightened, rejecting the world because the world made no sense. I hoped he would come to my middle school graduation.

I got into the Bishop’s School in La Jolla, the neighborhood where my mother had wanted to live when she first came to San Diego. The tuition was astronomical, and she would have to drive me forty minutes north and south every day. But nothing mattered more to her than my academic success.

At my middle school awards ceremony, Mom watched from the pews of the chapel as the principal-priest—a former actor who looked like a lean, handsome Santa Claus—introduced the valedictorian and salutatorian honors. He went on for what seemed like thirty minutes, with a booming voice and theatrical gestures, about how close the competition had been this year, how our class was the biggest eighth-grade class in the school’s history, how because of that there would be three winners instead of two. I tried not to throw up. The priest claimed he had done a bit of research and discovered a third-place award for rare cases like this one: a triusian. Immediately, I knew he had made the word up. I was sure I would be the recipient of his fiction.

“And the triusian is…”

My mouth dropped open when I heard the name. Matt? Matt looked around with a confused expression, shrugged, then walked up to accept the award. The priest cleared his throat to announce the next award. “And the salutatorian is…” I closed my eyes and tried to still my pounding heart. “Jean Guerrero!”

I walked up, my legs shaking with nerves and relief. At least I’m not the triusian, I told myself. At least I can commiserate with Matt. I shook the principal-priest’s hand and took my medallion. The final announcement came as I walked back to my seat, avoiding my mother’s gaze. The valedictorian was one of the Mexican boys who tormented me, one of the meanest bullies, whose father was an important person in Tijuana, later assassinated by members of a drug cartel. The middle school coordinator had repeatedly told us he was in the running for valedictorian, but I hadn’t believed her—I had seen a C and multiple B’s on his report cards.

I was relieved to discover, after the ceremony, that my mother was not mad at me. It’s not your fault this school is full of corruptos, she said, lip raised in repugnance. Other parents and classmates came up to me and said they knew I was the real valedictorian. I shrugged off the whole thing. So long as my mother wasn’t disappointed, I didn’t care. For all I knew, the Mexican boy really was the best-performing student. Perhaps I had imagined the bad grades on his report cards because of my bitterness about his bullying (he called me “ugly” more than anybody else, stabbed me with sticks and kicked soccer balls at my head for refusing to let him copy my answers on tests). While writing this, I didn’t think it was fair to include this scene without asking for the boy’s version of events. I found him on Facebook and wrote him a friendly greeting. He responded with a friendly greeting. When I explained why I was writing, the boy (now a man, of course) stopped responding. I followed up several times, to no avail. To this day, I don’t know what to believe. Was I blind to the intelligence of another child who toiled in silence? In the grand scheme of things, it was a silly middle school contest. It served me well to lose. I learned that nothing—no matter how badly you want it—is owed to you.

* * *

•

During the graduation ceremony, in my salutatorian speech, I thanked my mother and endeavored to inspire my classmates with platitudes. My voice shook. My braces were visible with each word. Stiff curls cascaded down my back. When I watch the video of the ceremony today, I feel a motherly sympathy for the girl I was in that long white dress: voice so breakable, hands quivering with a need to please. Papi didn’t show up until after the ceremony, when the school videographer had stopped recording and everyone was filing out of the pews. I recall seeing him enter the chapel with my Gucci-clad Abuela Carolina. He looked gaunt, in a simple black suit and his own camera around his neck. Suddenly, I could see no one but him. I gasped. Papi, you’re here.

* * *

•

That summer, I persuaded my mother to let me start horseback-riding lessons in the hunter/jumper style. Mom agreed to pay for them if Papi agreed to be my chauffeur. I hopped into his passenger’s seat, delighted by the situation. I sighed and slumped, trying to act fed up with the world—I wanted him to view me as a kindred spirit. But right away, I noticed his fiery eyes discerning the flaws in my performance. Like Mom, he saw right through me. Unlike her, he wanted nothing to do with me. My hopes deflated. I should have known: he was driving me to the barn because Abuela Carolina had ordered it. He declined to watch me ride.

I rode every day except Mondays, when the ranch was closed. Papi drove me to and from my lessons, mostly in silence. When I started at Bishop’s, he picked me up from La Jolla and dropped me off at the barn. I learned to jump and started competing in county shows. Mom noticed how much I loved riding and, after discussing it with my paternal grandmother, asked what I preferred on my fifteenth birthday: a quinceañera or a horse. Abuela Carolina agreed to pay for either. My mother would pay for board and feed. For my fifteenth birthday, I received Aspen, a bay mare with a white star on her forehead and a milk mustache marking. She was a Thoroughbred and quarter horse mix, with round dappled haunches that shone red in the sunlight.

I asked Papi if he wanted to see my horse. No thanks, he said. I was a teenager who guzzled Pepsi, listened to pop music and taped magazine pictures of male celebrities to her wall: vapid and typical, not at all the brilliant daughter he had envisioned when I was a curious toddler. Worst of all, I was the most spoiled person he had ever known. One day, when I was bragging about all of the first-place ribbons I was winning, he erupted: Yeah, yeah, you spoiled brat. Then he launched into a red-faced monologue describing all the ways in which I was shallow, spoiled and selfish. I was the most privileged individual in the history of our bloodlines, and had done nothing to deserve it. His vitriol sent me into a catatonic state of confusion.

Not everyone has Schizophrenic fathers, I wanted to say. Not everyone has mothers who use those fathers as a weapon against them.

But I remained silent. The months passed. The tensions of the unsaid accumulated. He offered to give me driving lessons in an empty parking lot. Every movement I made provided an excuse to attack me: I was stupid, distracted, lazy. A sudden rage awakened in my body as I wondered what gave him the right to criticize me. I shouted: You’re a nobody!

Only a few days later, Papi was gone again.

This time, he told his siblings where he was going: Southeast Asia. He sent a couple of postcards from Northern Thailand—one for my mother and one for his parents, both to my grandmother’s house. The one addressed to my mother pictured two grinning Thai children. In Spanish, Papi wrote: “Hi, Jeannette. I hope you’re well. I am well. Say hi to everyone. He who appreciates you, Marco.” I didn’t see Papi’s postcards until I was in my lat

e twenties, looking through old documents in a dusty chest at my grandmother’s house. Abuela Carolina either never delivered them to my mother or she told her about them and my mother declined to take them. My sister and I would remain ignorant of his whereabouts for two years. Again, we wondered if he was dead. I wanted to ask my father for forgiveness, but I had no way to reach him.

* * *

•

I obtained my driver’s license. My mother bought a minivan and gave me the keys to her BMW. I started driving myself to Imperial Beach, just a mile north of the U.S.-Mexico border. I threw myself into the cold waves, buoyed by the vastness, by the act of surrendering myself to the turbulent water. I purchased a bodyboard and rode the waves. At my new school, things had changed: I used to feel like the smartest girl in class, but at Bishop’s, everyone was smart. I started getting B’s on my report cards. At Bishop’s, all of the students seemed not only brilliant but rich. They lived in mansions in northern San Diego County, with spray tans and Chanel perfumes. I was one of only two people who commuted from Chula Vista. In middle school I had been called a gringa. At Bishop’s, I was essentially an immigrant. I looked forward each day to the barn, the one place I felt I could excel. I dreamed of an equine career, a life dedicated to taming beasts.

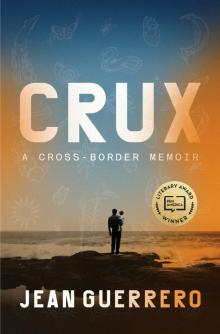

Crux

Crux